A Brief History of Botanical Illustration

A Brief History of Botanical Illustration

Over the centuries, the gap between the scientific and artistic depiction of plants has come together under the discipline of botanical illustration. This form of expression brings artists, inspired primarily by the outward beauty of plants, to a common ground with scientists, concerned about form more as it relates to a plant's function.

While the first botanical representation of plants dates back to bas-relief sculptures on the walls of the Egyptian Temple Karnak in 1500 BC, the depiction of plants was not of significant importance until the founding of Botany by the Greeks in 400 BC [1] . Founded as an area in which to study the medicinal properties of plants, physicians were the first to arrange botanical information. The first botanical book, known at the time as an Herbal, was De Materia Medica, arranged by the Greek physician Pedacius Dioscorides. Rather than being illustrated, the book described the appearance and medicinal properties of over 500 plants.

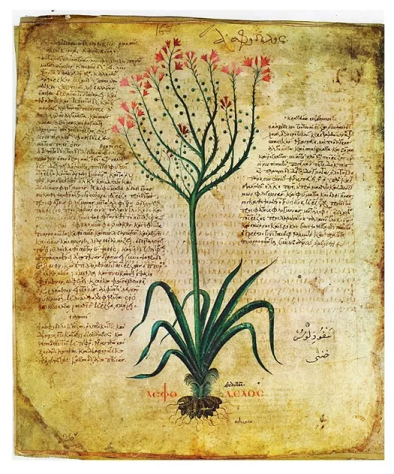

De Materia Medica was the principal botanical reference for over 500 years until its illustration in 512 AD, whereupon it became the well-known Codex Vindobonensis2. The Codex remained unrivaled in its scientific and artistic aspects for 1,000 years, despite the fact that two aspects of the book beckoned for improvement. First, although the Codex's brush drawings enhanced the verbal descriptions in portraying the plants, there was no perspective in their shading and they had an unnatural appearance [3] . Second, the hand-copying technique by which the book was reproduced allowed so much loss of detail that the original illustrations were distorted beyond recognition. The illustrations' copiers never actually viewed the plants themselves but made copies from copies .

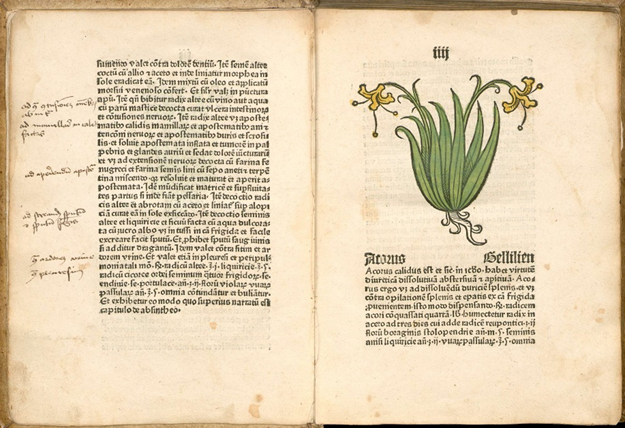

Advances in printmaking and the use of wood block print in 15th century Northern Europe helped with some of the copying troubles, but since illustrations were still copied from previous illustrations and then transcribed by a third person onto a wood block, there was still no advancement in illustration technique and detail continued to be lost in the copying process. Small details of the plants themselves were still not shown because of difficulties in the process- an artist would copy an illustration onto paper and hand it over to an engraver who would carve away the negative spaces of the print (those that won't apply ink to paper) from the block's surface for printing. The major herbal of this time was the German Herbarius, published in 1485.

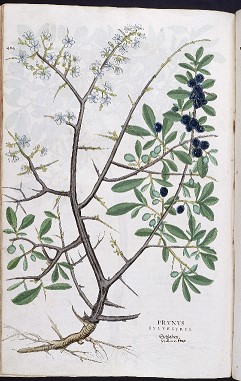

It wasn't until the mid-sixteenth century that artists began to draw from living plant materials. The somewhat idealized images of botanicals up until this time was partially a result of the use of dried specimens as subject matter, which left the artist to imagine the plant's lifelike state. Otto Brunfels' Herbarium Vivae Eicones, illustrated by the artist Hans Weiditz, represented a milestone in the emergence of botanical science and art as the first botanical to depict true-to-life plants- even if that meant torn leaves and wilted petals. Even such things were presented with sincere beauty3.

Leonhart Fuch's herbal De Historia Stirnium was another monumental addition to the discipline, noted for the delicacy of the lines in its illustrations, the 3-dimensional aspect from the artists' methods of shading, and the representation of all the natural features of the plants.

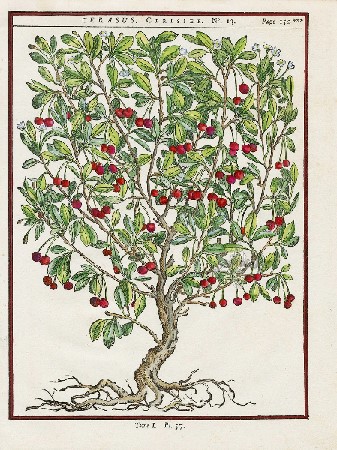

From Fuchs Botanical, 1545.

The end of the sixteenth century saw the production of many more herbals with woodcut illustrations including Pier Andrea Mattioli's Commentarii in sex libros Pedacii Dioscoridis in 1554, noted for its special attention to details like venation and texture and other works that featured the flowering and fruiting parts of plants, plant habitats, portrayals of life cycles, and depictions of the floral and vegetative parts of the plant together for identification purposes3. The inclusion of such information allowed the works to take on a new use: identification rather than simply ornamentation and decoration.

From this time, there was little advancement in the techniques used for botanical illustration until Thomas Bewick who lived from 1753-1828. Bewick used flat black areas and white lines to make features of the plant appear to rise out of the page in Thornton's New Family Herbal in 1810. Other illustrators of the time experimented with 3-dimensional techniques like aerial perspective and new methods of shading while detailed drawings of plant dissections made identification even more straightforward3. You may be familiar with Bewick, who is most famous for his illustrations of birds.

Aside from wood-block printing, etching and copper plate engraving were two other techniques used to reproduce illustrations. Although more expensive, these methods offered two advantages: the first being the fact that only one person did the original illustration and the plate etching, which eliminated some of the transcribing error, and the second being that these techniques allowed for the portrayal of features like small hairs, tiny parts, and other details which were often lost when the wooden blocks were whittled away1.

Copper Engraving by Besler, 1640

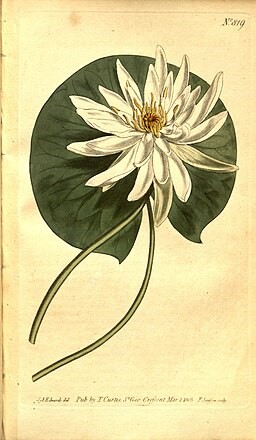

By 1777, botanical illustration came to inspire a great interest in gardening when publication of Kew Gardens' The Botanical Magazine began. William Curtis, the originator was the first to illustrate the publication with was released monthly with illustration of ten plants that each consumed an entire page. The plates used for printing were hand-tinted and reproduced with a fairly new technique- lithography. Lithography allowed for great strides in the inclusion of different tones in shaded areas, giving illustrations a much more appealing effect than line alone had before.

Nymphaealotus from Curtis's Botanical Magasine.

The next century saw the flourishing of painting to depict botanical forms and featured such artists as Pierre Joseph Redouté, noted for being the first artist to apply the stipple technique to floral art in copper, giving his works a tremendous sense of tactile reality. Taken under the patronage of Josephine Bonaparte, the wife of the famous Emperor Napoleon, Redouté published Les Roses and Les Liliacees, two of the most important works of botanical illustration even today.

The mainstreaming of photography in the twentieth century did nothing to diminish the value of botanical illustration as the medium for plant identification, analysis and classification. While no longer an essential tool to the physician or pharmacist, it is still of utmost importance to the botanical scientist, plant collector, gardener, designer, and natural historian [3] .

Botanical illustration is used not only to clarify descriptions of diagnostic characters of plants but is used to add works of artistic beauty to textbooks, museums, textiles, and decorating. The techniques also provide for a wonderful and relaxing leisure pursuit that has an enormous history of importance behind it.

This illustration from a 1989 edition of Kew Magazine (incorporating Curtis's Botanical Magazine) shows the evolving role of botanical illustration from primarily scientific to aesthetic and creative.

[1] King, Ronald. Botanical Illustration. Ash and Grant, Ltd., London. 1978.

[2] Ruff, Marion Elizabeth. Thesis: Methods and Techniques in Botanical Illustration. Cornell University Press, NY. 1950.

[3] Saunders, Gill. Picturing Plants: An Analytical History of Botanical Illustration. University of California Press, Berkeley. 1995.